Death Shall

Come on Swift Wings To Him Who Disturbs the Peace of

the King... -Supposedly engraved on the exterior

of King Tutankhamen's Tomb

The king

was only nineteen when he died, perhaps murdered by

his enemies. His tomb, in comparison with his contemporaries,

was modest. After his death, his successors made an attempt

to expunge his memory by removing his name from all the

official records. Even those carved in stone. As it

turns out, his enemy's efforts only ensured his

eventual fame. His name was Tutankhamen: King Tut.

The ancient Egyptians revered their Pharaohs as

Gods. Upon their deaths the King's bodies were carefully

preserved by embalming. The mummified corpses were

interned in elaborate tombs (like the Great Pyramid) and

surrounded with all the riches the royals would need in

the next life. The tombs were then carefully sealed.

Egypt's best architects designed the structures to

resist thieves. In some cases heavy, hard-granite

plugs were used to block passageways. In others,

false doorways and hidden rooms were designed to fool

intruders. Finally, in a few cases, a curse was placed

on the entrance.

Most of these precautions

failed. In ancient times grave robbers found their

way into the tombs. They unsealed the doors, chiseled

their way around the plugs and found the secrets of

the hidden rooms. They stripped the dead Kings of

their valuables. We will never know if any of the thieves suffered

the wrath of a curse.

Archaeologists

from Europe became very interested in Egypt in the

19th century. They uncovered the old tombs and

explored their deep recesses always hoping to find that one

forgotten crypt that had not been plundered in antiquity. They

knew that the Pharaohs had been buried with untold

treasures that would be of immense artistic,

scientific, and monetary value. Always the

archaeologists were disappointed.

The Search for the

Missing King

In 1891 a young Englishman

named Howard Carter arrived in Egypt. Over the years

he became convinced that there was at least one

undiscovered tomb. That of the almost unknown King

Tutankhamen. Carter found a backer for his tomb search

in the wealthy Lord Carnarvon. For five years Carter dug looking

for the missing Pharaoh and found nothing.

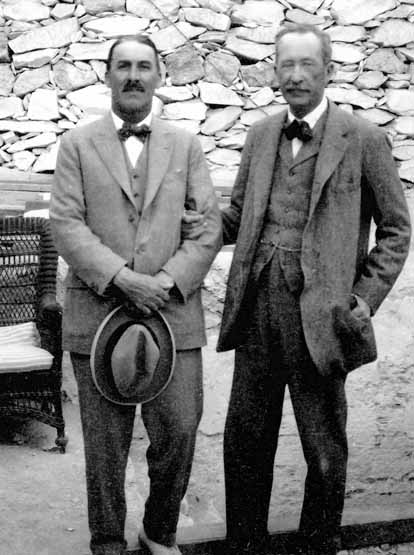

Carter and Carnarvon

Carnarvon summonded Carter to England

in1922 to tell him he was was calling off the search.

Carter managed to talk the lord into supporting him

for one more season of digging. Returning to Egypt

the archaeologist brought with him a yellow canary.

A Few Authentic Curses from

Mummy Tombs

As for any man who shall destroy these, it is the god Thoth who shall destroy him. As for him who shall destroy this inscription: He shall not reach his home. He shall not embrace his children. He shall not see success. |

"A

golden bird!" Carter's foreman, Reis Ahmed,

exclaimed. "It will lead us to the tomb!"

Perhaps it did. On November 4th, 1922 Carter's

workmen discovered a step cut into the rock that had been hidden

by debris left over from the building of the tomb of

Ramesses IV.. Digging further they found fifteen more

leading to an ancient doorway that appeared to be

still sealed. On the doorway was the name

Tutankhamen.

When Carter arrived home that

night his servant met him at the door. In his hand he

clutched a few yellow feathers. His eyes large with

fear, he reported that the canary had been killed by a

cobra. Carter, a practical man, told the servant to

make sure the snake was out of the house. The man grabbed

Carter by the sleeve.

"The pharaoh's

serpent ate the bird because it led us to the hidden

tomb! You must not disturb the tomb!"

Scoffing

at such superstitious nonsense, Carter sent the man

home.

Carter immediately sent a telegram to

Carnarvon in England and waited anxiously for his

arrival. Carnarvon made it to Egypt by November 26th

and watched as Carter made a hole in the door. Carter

leaned in, holding a candle, to take a look. Behind

him Lord Carnarvon asked, "Can you see anything?"

Carter

answered, "Yes, wonderful things."

The

day the tomb was opened was one of joy and

celebration for all those involved. Nobody seemed to be concerned

about any curse. Rumors later circulated that Carter had

found a tablet with the curse inscribed on it, but

hid it immediately so it would not alarm his workers.

Carter denied doing so.

The

tomb was intact and contained an amazing collection

of treasures including a stone sarcophagus. The sarcophagus

contained three gold coffins nested within each other. Inside

the final one was the mummy of the boy-king, Pharaoh

Tutankhamen.

The

Curse Strikes?

A

few months after the tomb's opening tragedy struck.

Lord Carnarvon, 57, was taken ill and rushed to Cairo.

He died a few days later. The exact cause of death was not known,

but it seemed to be from an infection started by an

insect bite. Legend has it that when he died there

was a short power failure and all the lights

throughout Cairo went out. His son reported that back

on his estate in England his favorite dog howled and

suddenly dropped dead.

Even more strange,

when the mummy of Tutankhamun was unwrapped in 1925,

it was found to have a wound on the left cheek in the

same exact position as the insect bite on Carnarvon

that lead to his death.

By 1929 eleven people

connected with the discovery of the Tomb had died

early and of unnatural causes. This included two of

Carnarvon's relatives, Carter's personal secretary, Richard

Bethell, and Bethell's father, Lord Westbury. Westbury killed

himself by jumping from a building. He left a note that

read, "I really cannot stand any more horrors and

hardly see what good I am going to do here, so I am

making my exit."

What

horrors did Westbury refer to?

The

press followed the deaths carefully attributing each

new one to the "Mummy's Curse" By 1935 they had credited

21 victims to King Tut. Was there really a curse? Or was it

all just the ravings of a sensational press?

Herbert E. Winlock, the director of the Metropolitan

Museum of Art in New York City, made his own calculations about

the effectiveness of the curse. According to to

Winlock's figures of the 22 people present when the

tomb was opened in 1922, only 6 had died by 1934. Of

the 22 people present at the opening of the

sarcophagus in 1924, only 2 died in the following ten

years. Also ten people were there when the mummy was unwrapped

in 1925, and all survived until at least 1934.

In 2002 a medicine scholar at Monash University

in Melbourne, Australia, named Mark Nelson, completed a study

which purportedly showed that the curse of King Tut never

really existed. Nelson selected 44 Westerners in

Egypt at the time the tomb was discovered. Of those,

twenty-five of the group were people potentially

exposed to the curse either because they were at the

breaking of the sacred seals in the tomb, or at the

opening of the sarcophagus, or at the opening of the

coffins, or the unwrapping of the mummy. The study showed that

these exposures had no effect on the length of their survival

when compared to those not exposed.

Perhaps,

the power of a curse is in the mind of the person

who believes in it. Howard Carter, the man who actually

opened the tomb, never believed in the curse and lived to a

reasonably old age of 66 before dying of entirely natural

causes.

A

Rational Explaination?

Several people have

suggested that illnesses associated with the ancient

Egyptian tombs may have a rational explanation based

in biology. Dr. Ezzeddin Taha, of Cairo University, examined

the health records of museum workers and noticed that many of

them had been exposed to Aspergillus niger, a

fungus that causes fever, fatigue and rashes. He

suggested that the fungus might have been able to

survive in the tombs for thousands of years and then

was picked up by archaeologists when they entered.

Dr. Nicola Di Paolo, a Italian physician identified

another possible fungus, Aspergillus ochraceus,

at Egyptian archaeological sites suggesting it might

also have made visitors to the tomb, or even those

that just handled artifacts from the tombs, sick. Aspergillus

ochraceus has not been shown to be fatal,

however.

In 1999 a German

microbiologist, Gotthard Kramer, from the University

of Leipzig, analyzed 40 mummies and identified

several potentially dangerous mold spores on each. Mold spores

are tough and can survive thousands of years even in a dark,

dry tomb. Although most are harmless, a few can be

toxic.

Kramer thinks that when tombs were first

opened and fresh air gusted inside, these spores

could have been blown up into the air. "When spores

enter the body through the nose, mouth or eye mucous

membranes, " he adds, "they can lead to organ failure

or even death, particularly in individuals with

weakened immune systems."

For this reason

archaeologists now wear protective gear (such as

masks and gloves) when unwrapping a mummy, something

explorers from the days of Howard Carter and Lord Carnarvon

didn't do.

So was the curse of the mummy a

mold spore named Aspergillus flavus or Cephalosporium?

Or was it all media hype? Or is there another

explaination?

from UnMuseum.org

0 comments:

Post a Comment